Схема Хэ-Ту. Дыхание в духовных традициях народов мира

«Щедрик»

в опрацюванні М. Леонтовича

Спроба полівекторного аналізу

“Shchedryk” elaborated by Mykola Leontovych. Polyvectoral Analysis

Валентина Кузик,

доктор філософії (з мистецтва), старший науковий співробітник відділу

музикознавства та етномузикології Інституту мистецтвознавства,

фольклористики та етнології ім. М.Т. Рильського НАН України, лауреат

Премії ім. М.В. Лисенка, член Національної спілки композиторів

України

Valentyna Kuzyk, Doctor of Philosophy (Arts), Senior Researcher at the Department of Musicology and Ethnomusicology of M.T. Rylskyi Institute of Art, Folklore Studies and Ethnology of NAS of Ukraine, laureate of M.V. Lysenko Prize, member of the National Union of Composers of Ukraine

«Те, що

важко переказати словом і співаницею, вона сподобляється передати

вузликами барв і ладом узорів. Либонь, і сама не знає, звідки це

точиться. Просто безпомильно «списує» те, що бачить зряче

серце, що нашіптують їй давні голоси. І так ця красна правда

перетікає з віку у вік, з роду в рід. Милує око й наповнює свіжою

радістю серце».

Мирослав Дочинець «Карби і скарби»

«Щедрик» в опрацюванні Миколи Леонтовича став унікальним явищем світової культури. Він привернув увагу мільйонів, з-поміж яких були й музиканти, фольклористи, філологи, філософи та теологи. Первісний архетип із серії так званих народних примітивів наші пращури від язичницьких часів вважали магічною формулою – мантрою, що заворожувала, гіпнотизувала людину. Головними психологічними чинниками дії цієї «магії» були незмінна повторюваність мотиву – оstinato-stabilіtas – та безперервність руху – perpetuum mobile. Навіть сила слова (verbe) поступилася перед музично-психологічним началом. Це явище, переконана, привернуло увагу такого геніального Майстра від музики, як М. Леонтович, коли він обирав зразки для свого композиторського шкіца.

Вивчення нотного тексту «Щедрика» дозволило вирізнити 5 векторів аналізу, зокрема й не зовсім типових для музикознавчого ока (без сумніву, при достатній прискіпливості їх може бути більше), а саме: 1) історичний; 2) музичний; 3) вербальний; 4) графічний; 5) нумерологічний.

“With

knots of colours and strokes of patterns, she manages to convey what

cannot be rendered by a word or song. She does not seem to be aware

herself of where does it come from. She just immaculately “transmits”

what a heart sees, what distant voices whisper her. This is how this

beautiful truth circulates through ages and generations. It leases

the eye and invigours the heart with lively joy.”

Myroslav

Dochynets “Karby i skarby” (Milestones and Treasures)

“Shchedryk”

elaborated by Mykola Leontovych has

become a unique phenomenon of

world culture. It has captured attention of millions, including

musicians, folklorists, philologists, philosophers and theologians.

Our ancestors of pagan times perceived the original archetype that

formed part of a series of so-called folk primitives as a

magic

formula-mantra that mesmerized, hypnotized a human. The

major psychological factors for the effect of such a “magic”

were the constant tune repetition (оstinato-stabilіtas) and

continuity of movement (perpetuum mobile). Even the power of a word

(verbe) gave way to the musical and psychological source. To my mind,

this phenomenon aroused interest of such an ingenious master of music

as M. Leontovych, when he selected samples for his composer’s

sketch. The study of the musical text of “Shchedryk has made it

possible to distinguish 5 vectors of analysis, including not that

typical for a musicologist (there may be, undoubtedly, more of them

in case of more meticulous examination), specifically:

1) historical; 2). musical; 3) verbal; 4) graphic; 5) numerological.

І.

Історичний вектор. Рукопис «Щедрика», надісланого

Олександрові Кошицю, датовано 18 серпня 1916 року. Я. Юрмас (Юрій

Масютин) зазначав, що текст узято зі «Збірничка найкращих

українських пісень з нотами»

К. Поліщука й М. Остаповича

(1913 р., ч. ІV, № 23, с. 18) [1].

Проте за згадкою Болеслава Яворського поліфонічні вправи з остинатним мотивом «Щедрик» було розпочато ще 1910 р. Логічно припустити: М. Леонтович обрав знайомий із дитинства фольклорний зразок, що побутував на Поділлі (мабуть, і сам змалку защедрував не одну цукерку). Зі збірки К. Поліщука й М. Остаповича він узяв тільки слова, записані збирачами в м. Краснопіль Житомирського повіту Волинської губернії. (Що ж, музиканти завжди гірше запам’ятовували слова, аніж наспів).

Знайомство з надрукованим текстом дало простір митцю для більш широкого розгортання музичного матеріалу, а можливо, і зміни первісної поліфонічної концепції будови на синтетичну – з уведенням гармонічно-акордових прийомів [2]. Як бачимо, процес опрацювання «Щедрика» тривав протягом 6 років. Недаремно! Феноменальний успіх у київських концертах на Різдвяні свята хору студентів Свято-Володимирського університету під орудою О. Кошиця в 1916 р. (за ст. стилем 25 грудня 1916 року, тобто за новим стилем 7 січня 1917 року) став для «Щедрика» першим щаблем сходження до світової слави1.

ІІ. Музичний вектор. Головне зерно твору – чотиризвучний мотив-мантра. Він повторюється з проведенням у всіх партіях 68 разів! М. Леонтович використав розмаїті техніки композиторського письма, не порушуючи однак головного принципу perpetuum mobile – оstinato, що надзвичайно рідко зустрічаємо в музиці митців початку ХХ століття.

ІІІ. Вербальний вектор. На сьогодні утвердилося три варіанти тексту «Щедрика» (ще в 1920-ті роки за кордоном були спроби зробити переклади української щедрівки французькою, німецькою, англійською, але вони ненадовго прижилися в культурному обігу) [3].

Текстове першоджерело має зв’язок із дохристиянською добою, коли новий рік починався ранньої весни – із поверненням в Україну ластівок (тобто з 14 березня). Цікаво, що композитор подає слова «щедрик», «щедрівочка» тільки тематично, і це особливо посилює їх психологічну дію. Вони насправді мають таку «ароматну» силу вербального звучання2, що під час використання в інших шарах могли б «замулити» загальний колорит. Цікаво, що в п’ятому куплеті композитор узяв слова «В тебе жінка хороша», однак до вибору було ще «Хоч не гроші, то полова»3. Ніби й деталь, але показова!

2. Мало кому відомо, але ми маємо й другий текстовий варіант – «Ой на річці, на Ордані». Його записано добрим знайомцем М. Леонтовича, учителем співу з Тульчина Федором Лотоцьким у с. Паланка Гайсинського повіту на Поділлі в грудні 1916 року [4]:

Ой

на річці, на Ордані,

Там Пречиста ризи прала,

Свого Сина

сповивала.

Прилетіли три янголи,

Взяли Йсуса на небеса…

I. Historical vector. The manuscript “Shchedryk” sent to Oleksandr Koshyts is dated August 18, 1916. Y. Yurmas (Yurii Masiutyn) noted that the text was adopted from “The Collection of Best Ukrainian Songs with Notes” by K. Polischuk and M. Ostapovych (1913, part IV, No. 23, p. 18). However, as Boleslav Yavorskyi recalls, polyphonic exercises with the ostinato tune “Shchedryk” appeared as far back as 1910. It is logical to presume that M. Leontovych chose a familiar from his childhood folk sample that was common in Podillia region (perhaps, when a child he also went carolling for candies). Leontovych adopted from the collection by K. Polischuk and M. Ostapovych only words recorded by folksongs’ keepers in the city of Krasnopil of Zhytomyr county, Volyn region. (Well, musicians have always remembered words worse than tunes). Learning a printed text has given the artist space to larger expand musical material, and, possibly, transform its original polyphonic structural concept to the synthetic one with the introduction of harmonious and chord techniques. It gives us the reason to conclude that the process of elaborating “Shchedryk” lasted 6 years. Not for nothing! The phenomenal success of the students’ choir of St. Volodymyr’s University headed by O. Koshyts at Christmas festivals in Kyiv in 1916 (December 25, 1916 in the Julian calendar, that is January 7, 1917 in the Gregorian calendar) has become for “Shchedryk” the first step on the way of gaining the worldwide fame1.

II. Musical vector. The gist of the work is a four-tone tune-mantra. It is repeated 68 times in all sections! M. Leontovych applied various techniques of composer’s writing, though did not violate the main principle of perpetuum mobile – ostinato, which is rather rare for musical works of artists of the early 20th century. ІІІ. Verbal vector. Today, three versions of the text of “Shchedryk” have been recognized (as early as the 1920s, there were made attempts to translate the Ukrainian carol into French, German, English, yet they soon failed to get customized in the cultural circles). The primary source of the text is connected with the pre-Christian era, when the New Year began in the early spring – when swallows returned to Ukraine (believed to be March 14). It is noteworthy that the composer put words “Shchedryk”, “Shchedrivochka” only thematically, which makes it psychologically more powerful. In fact, they indeed have so “fragrant” force of verbal sound2 that when used in other layers, they could “muddy” the whole flair. Curious is that the composer chose the words “You have a good wife” for a fifth couplet, although there were other options: “If not money, then chaff”3. It seems to be a trifle, but it is so revealing!

2. Very few know about a second text version – “On the river, on the Ordana”. It was written by a good acquaintance of M. Leontovych Fedir Lototskyi, a singing teacher from Tulchyn, in Palanka village of Haisynskyi county in Podillia, in December 1916.

On

the river, on the Ordana,

Holy Mother washed the robe,

Swaddled

her Holy Son.

Three angels flew in,

Took Jesus to heaven…

Поширення цієї текстової версії в середовищі подільської інтелігенції, духівництва, селян засвідчило жанрову метаморфозу твору, а саме – переведення його зі щедрівок до колядок, пов’язаних із темою народження Христа. Інша географія, інша пора року. Цю текстову версію вже в наш час – від 1980-х років уперше представив із хором «Відродження» відомий хормейстер і науковець Мстислав Юрченко, після чого її підхопили хори «Київ», «Хрещатик», «Пектораль», ансамблі «Фавор», «Аніма» та чимало інших колективів.

3. Після тріумфальної ходи світами разом із капелою О. Кошиця (то окрема й довга оповідь!) наш «Щедрик» отримав англомовну версію тексту4. Ні, це не переклад з української, а цілком оригінальний вірш, відповідний жанру колядок, і співалося в ньому про різдвяні дзвони: «Hark how the bells» / «Виразно чути дзвіночки». Його в 1930-ті рр. склав диригент-хормейстер, учитель музики Пітер Вільховський (прізвище красномовно свідчить про етнічне походження автора слів), а надрукувала вперше слова з музикою фірма «Carl Fisher, Inc.» у США в 1936 р. під назвою «Carol of the Bells» – «Колядка дзвіночків». Названий хормейстер при створенні нових слів свідомо обрав зрозумілий для американської ментальності символ зимового свята – різдвяні срібні дзвіночки – та пов’язані з ним картини засніженого чарівного лісу, санчат із дарунками. Думка виявилася слушною! Слова прижилися на новому національному й континентальному ґрунті. Ба більше, із часом «Колядку дзвіночків» американці стали вважати власною народною творчістю:

Hark how the

bells

Sweet silver bells

All seem to say

Throw cares away…

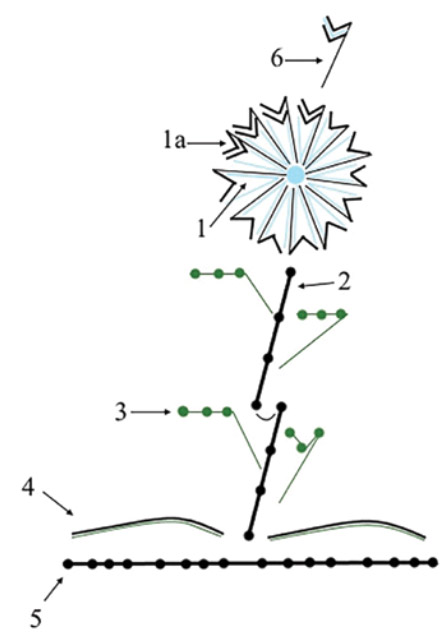

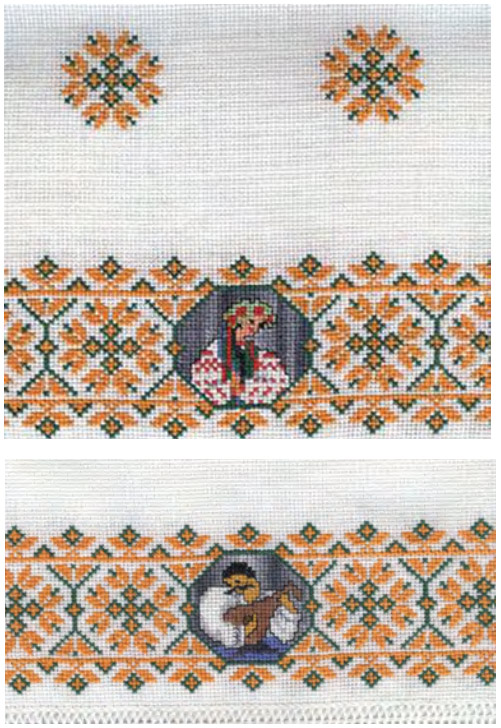

Щоправда, український «Щедрик» в англомовній версії звучить дещо «hard» – твердіше й дійовіше5. ІV. Графічний вектор. Імпульсом для нього стали дослідження у сфері синтезу мистецтв, зокрема світломузика, якою в короткий «київський період» життя протягом 1919–1920 рр. переймався й М. Леонтович. Нині експериментальні пошуки в цій галузі вийшли на рівень створення художніх картин за нотними текстами, де відповідно до кожної ноти – її висоти-кольору й тривалості – вимальовуються образотворчі полотна6. Вивчення природи й таїни «конструювання символічної образності» [5], яким надавали великого значення Й. Ґете, К.Г. Юнг, П. Флоренський, О. Лосєв та інші світлі уми, спонукало до думки шукати знаки й у музиці Леонтовича. Відомо, що твори М. Леонтовича деякі дослідники й поети називають «діамантом, ограненим рукою Генія». Я маю скромніші статки до порівняння, але не менш цінні за значимістю – це українські вишивки й силянки-ґердани, що вправно мережать золоті руки наших майстрів. Тому мені, як великій шанувальниці вишивки й силянки, забажалося поглянути на Леонтовичевого «Щедрика» в графічних орнаментальних образах. Диво – його поспівки перевтілилися в абриси ніжної квітки, що зростала вертикально вгору. У ній яскраво виокремилися 6 елементів:

1)

споконвічне «зерно» в прямому виді, де 68 повторів (зокрема

й виокремлений останній) – 68 «бутон-пуп’янок»;

1-а) рефлексія «зерна» – верхньотерцієвий

підголосок (сопрано: «В тебе товар весь хороший…»);

2)

лінеарне «стебло» – спочатку низхідний рух в альтів

(«Стала собі»), а далі – в альтів і тенорів

(«щебетати»);

3) листячко із «зубчиками»-акцентами

(«В тебе товар весь хороший…»);

4) хвилясті

«трави-ковилі» (сопрано: «В тебе жінка

чорноброва»);

5) ґрунт – бурдон (бас: «В тебе

товар весь хороший»);

6) бутон-пуп’янок (дует coda:

«ластівочка»).

Можна збагатити малюнок квітки

напластуванням всіх 67-ми мотивів-пелюсток (бо останній 68-й –

coda). Суттєвий феномен – універсальні закони людського

мислення виявилися спільними як для музичного інтонування, так і для

графічного малюнку. Вони оформилися в одвічний символ-орнамент

«Квітки життя» з бутоном-пуп’янком –

паростком у майбуття, який так люблять вишивати на рушниках наші

майстрині, вимальовують художники з Петриківки на полотнах, на

кераміці – гончарі, а на дерев’яних виробах –

різьбярі. Відома дослідниця українських орнаментів, лауреатка

Національної премії ім. Тараса Шевченка п. Зоя Чегусова зазначає: «…

квітку у світовому мистецтві вважають символом земної кулі або центра

всесвіту, як результат – архетиповим символом душі. Квіти також

є поширеними

символами молодого життя і сонця, вони уособлюють

життєву силу і радість буття, кінець зимового стану природи і

перемогу над смертю. Любов до квітів зробила їх майже об’єктом

культу нашого народу. Квітами супроводжується все життя українців –

від народження до смерті» [6]. Згодом було додано нову

візуальну інформацію, що дозволила мені асоціативно вирішити проблему

змалювання квітки «Щедрик». А саме – розкішна

троянда південного порталу собору Паризької Богоматері. Вона утворює

«квітку – сонячну розетку». Розширюючи значення

символу солярної квітки-розетки, що є в багатьох

The fact that intellectual circles, clergy, and peasants of Podillia were familiar with this version of the text proved that a genre metamorphosis of the work, namely, its transition from Christmas carols to carols concerned with the birth of Jesus Christ theme. Another geography, another season. This text version was for the first time presented already in recent times, since 1980s, by Mstyslav Yurchenko, a famous choirmaster and scholar, with the choir “Vidrodzhennia” (Renaissance), after which followed the choirs “Kyiv”, “Khreshchatyk”, “Pectoral”, ensembles “Favor”, “Anima” and many other artistic groups.

3.

After “Shchedryk” along with the chapel of A. Koshyts (it

a long story of its own!) made itself known to the world, it received

the English version of the text4.

No, this was not a translation from the Ukrainian, but quite an

authentic poem of a carol genre, telling about Christmas bells -

“Hark how the bells”. It was created by

conductor-choirmaster, music teacher Peter Wilhousky (his surname

glaringly testifies to the author’s ethnic origin) in the

1930s, while the words with music were first published by “Carl

Fisher Inc.” company in the USA in 1936, receiving the name

“Carol of the Bells”. When composing new words for the

carol, the above-mentioned choirmaster purposely chose silver

Christmas bells as a symbol of the winter holiday and the associated

with

them images of snowy charming forest, sledges with gifts and

so on, which are inherent in the American mentality. It turned out to

be the right idea! The words have become common in a new nation and

continent. All the more so, as time passed, Americans started

consider “Carol of the Bells” their own folk art:

Hark

how the bells

Sweet silver bells

All seem to say

Throw cares

away…

Still, it appears that Ukrainian “Shchedryk” sounds somewhat “hard” in the English version – harder and more active5.

ІV.

Graphic vector. The impetus for such a vector was the research in the

area of synthesis of arts, particularly light music, in which M.

Leontovych among other things took interest during a short “Kyiv

period” of life in 1919–1920. Today, the experimental

searches in this field have grown into creating artistic images

according to musical texts, in which each note – its height,

colour and duration, is reflected in artistic canvas6.

Study of the nature and mystery of “designing symbolic

imagery”, which was of great importance to J. Goethe, K.G.

Jung, P. Florenskyi, O. Losiev and other bright minds, suggested to

seek signs in musical works of Leontovych. It is known that his works

are called by some researchers and poets as “a diamond polished

by hand of a Genius”. I am

rather modest when it comes to

comparisons, but nonetheless meaningful – these are Ukrainian

embroideries and “syliankas”, “gerdanas”

(beaded necklace), which dexterously adorn skilful fingers of our

craftsmen. This is why, being a huge admirer of embroidery and

“sylianka”, I wished to take a look at Leontovych’s

“Shchedryk” through graphic ornamental images. However

amazing it was, his songs turned into outlines of a gentle flower

that grew upright. There are 6 elements clearly differentiated in it:

1) an original

“grain”

in its regular form with 68 repetitions (including the separate last)

– 68 “petal-bud”; 1-a) reflection of a “grain”

– upper-tierce echo (Soprano: “Your goods are all

good...”); 2) a linear “stem” – first a

descending motion in altos (“Became on its own”), and

then – in altos and tenors (“twitter”); 3) a

leaflet with “serrations”-stresses (“Your goods are

all good...”); 4) wavy “Stipa grass” (Soprano:

“Your wife is blackbrowed”); 5) soil – drone

(bourdon) (Baso: “Your goods are

all good”); 6) bud

(duo coda: “swallow”). One may enlarge the flower image

with adding all 67 petal tunes (as the last 68th is coda). A crucial

phenomenon is that the universal laws of human reasoning appeared to

be common for both musical tone and graphic image. They have

consolidated into an eternal symbol-ornament of the “flower of

life” with a bud – a sprout reaching out to the future,

which Ukrainian craftswomen eagerly embroider on towels, artists from

Petrykivka paint on canvas, potters apply to ceramics, carvers

engrave on woodware. Zoia Chehusova, a famous Ukrainian researcher in

ornaments, laureate of the Taras Shevchenko National Prize, remarks,

“... a flower in world art is deemed as a symbol of the globe

or a centre of the universe, and consequently an archetypal symbol of

the soul. Flowers are also a widely used symbol of the youth and sun;

they embody the vitality and the joy of life, the end of winter

season and the victory over death. The love for flowers made them

nearly a sacred object of our people. Flowers accompany Ukrainians

throughout whole their lives – from birth to death.”

Subsequently, a new visual reference complemented the research, which

has allowed me to resolve the problem of drawing “Shchedryk”

flower by association. It was a marvellous rose of the southern

portal of Notre-Dame de Paris. It forms a “flower – a

sunlit rosette”. If to expand the meaning of the symbol of the

solo rosette flower, which is peculiar to many cultures of peoples

around the world, one may notice

Ілюстрація

№ 1. Квіточка «Щедрик»

Illustration No. 1. “Shchedryk”

flower

Ілюстрація № 2. Фото розетки собору Паризької

Богоматері

Illustration No. 2. Photo of rosette of Notre-Dame de

Paris

культурах

людства всієї планети, вбачаємо його вживання в сакральних знаннях,

де він означає первісний символ душі (духу), а саме – «повітря

– дихання», сила космічної життєвої енергії (як на

санскриті, так і давньоукраїнською це звучало так – «хара»;

згадаймо, «характерниками» називалися люди, які володіли

цією силою). Такий символ бачимо на поясній хустині, вишивці на

грудях, рукавах, покрові голови Богоматері Оранти в куполі

Софійського собору (Софія – вища премудрість), намолених іконах

Богоматері. Його модифікацію як хреста з розширеними на кінцях

раменами зафіксували хрести Мальтійського ордену та запорозького

козацтва, нагородні хрести сучасної України. Вишивані символи

солярної квітки-хреста прикрашають святкові ризи ієреїв вищого сану.

Символ «дихання – хари» бачимо й в узорі

української вишивки, зафіксованому письменницею та етнографом Оленою

Пчілкою – матір’ю Лесі Українки. Принагідно зауважу, що

цей універсальний для людства символ «сонячної розетки»

став «фірмовим» знаком унікального методу лікування

видатного українського медика Костянтина Бутейка, який вбачав у ньому

концентроване графічне зображення Вищого розуму та його перемогу

над

безглуздям. Тож відповідно до французької розетки-троянди я перевела

в графіку квітку «Щедрик». Однак, якщо точно йти за

абрисом нотної лінії, виходить не троянда, а пишна поліська волошка

із загостреними кінчиками пелюсток. Спробувала те намалювати: у

внутрішньому колі 23 пелюстки, у зовнішньому – 44. А останній

пелюсток-«ластівочка» – злетів догори. V. Отже,

бодай «на око», нумерологічний вектор аналізу, розробкою

якого займалися античний Піфагор, геній Відродження Леонардо да Вінчі

та сучасні Г. Гессе й Д. Браун. Вони стверджували, що вирахувати

можливо все! Адже все, що породжує абстрактне узагальнення, може

стати

that

it is used in sacred knowledge, meaning the primal symbol of the soul

(spirit), namely “air – breathing”, the power of

cosmic life energy (it sounded as “hara” both in Sanskrit

and the Old Ukrainian; which reminds us of people possessing this

power, who were called “characters”). This symbol is on

the waist scarf, embroidery on the chest, sleeves, head veil of the

Virgin Orans on the dome of St. Sophia Cathedral (Sofia means “the

highest wisdom”), sacred icons of Our Lady. Its modification in

the form of a cross with extended arms at the ends was embedded in

crosses of the Order of Malta and Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, honouring

crosses of today’s Ukraine. Festive robes of high-ranking

priests are decorated with embroidered symbols of the solo rosette

flower. The symbol “breathing – hara” is also

present in the pattern of Ukrainian embroidery, which was recorded by

writer and ethnographer Olena Pchilka, a mother of Lesia Ukrainka.

Therewith, I would like to note that this universal for mankind

symbol of the “sunlit rosette” has become a “brand”

mark of the unique method of treatment by Kostiantyn Buteiko, a

distinguished Ukrainian physician, who viewed this mark as a graphic

representation of the Higher Reason and its victory over nonsense.

In

such a way, by the example of the image of the French rose rosette, I

transformed “Shchedryk” flower into a graphic image.

However, the image turned out to be not a rose, but a cornflower of

Polissia or Centaurea cyanus with pointed petals, if to follow

strictly the musical staff. I tried to draw it: 23 petals in the

inner circle, 44 petals in the outer circle, and the last petal -

“swallow bud” soared up. V. Numerological vector of the

analysis (yet roughly estimated) that was once developed by the

ancient Pythagoras, genius the Renaissance era Leonardo da Vinci, and

bright minds of the present H. Hesse and D. Brown. They argued that

everything is possible to be calculated! Likewise, everything

Ілюстрація № 3.

Богоматiр Орантa в куполі

Софійського собору

Illustration No.

3. The Virgin Orans on the dome

of St. Sophia Cathedral

Ілюстрація

№ 5. Малюнок розетки «Щедрик»

Illustration No. 5.

Image of “Shchedryk” rosette

Ілюстрація № 4. Вишивка

на рушнику

Illustration No. 4. Embroidery on a towel

символом:

як елементи природи, фізичного світу, космосу, так і уявні абстракції

– літери, цифри, переплетіння ліній та звуків, породжені

позасвідомою мудрістю людства, що тягнеться впродовж тисячоліть і

виявляє себе з особливою пасіонарністю у творіннях геніїв. Відомо,

яке вагоме сакральне значення мають цифра й число у Святому Письмі та

інших сокровенних сакральних знаннях. Їх там шанобливо називають

«фігурою». Не останню роль у моєму бажанні звернутися до

нумерології зіграло вмотивування М. Леонтовичем пісні «Дударик»

як позасвідомого музичного авторського образу (звукового

«автопортрету»), де текст і наспів відповідали його

художній природі, а число «сім» було кодовим – «на

щастя, на долю». Ще більше вразив підрахунок виокремлених мною

тематичних зерен у «Щедрику»: 68 разів повторено «зерно»

+ 4 рази показано його верхньотерцієве віддзеркалення + 1 раз у коді

= 73, що при перерахуванні 7 + 3 = 10; цифру 0 не враховують, тож

залишається число 1 = символ «Deus», «Бог».

Дивним чином знову вийшли на універсальні загальнолюдські ідеї.

На

завершення дозволю висловити думку: у зв’язку з тим, що за

програмою ЮНЕСКО у реєстр заносять усі вагомі національні культурні

явища, закликаю небайдужих українців звернутися до цього

високошановного органу з пропозицією про визнання «Щедрика»

Миколи Леонтовича духовним надбанням людства. Це було б гарним

дарунком до 100-річчя світових мандрів народного пісенного діаманта й

визнання геніального Майстра з Поділля.

that

results in abstract concepts may turn into a symbol: either of

natural elements, or the physical world, space, or of imaginary

abstractions – letters, numbers, interweaving of lines and

sounds originated from the unconscious wisdom of mankind, which have

been existing throughout millennia and represents itself in works of

geniuses with a special passion. It is known that in the Holy

Scripture and other intimate knowledge, a figure and a number have a

critical sacred meaning. They are honourably called “figures”.

I was much inclined to resort to numerology because of the tune

introduced by M. Leontovych in the song “Dudaryk” as an

unconscious author’s musical image (sonic “self-portrait”),

in which the text and tune corresponded to his artistic nature, and

the number “seven” was a code – “for

happiness”, “for luck”. Still I was more impressed

by the calculation of the thematic grains I indicated in “Shchedryk”:

the “grain” was repeated 68 times + its upper-tierce echo

took place 4 times + 1 time in a code = 73, which when recalculating

equals to: 7 + 3 = 10; the figure 0 does not count, thus the number 1

remains as the symbol “Deus”, “God”.

Surprisingly, we have again arrived at universal human ideas. To

conclude, I would like to ask all concerned Ukrainians to appeal to

such a high-ranking institution as UNESCO to recognize “Shchedryk”

by Mykola Leontovych as the spiritual heritage of the mankind, taking

into account that the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage

registers all significant national cultural phenomena. This would be

a great gift to the 100th

anniversary of global travels of the national song diamond and

acknowledgement of the genius artist of Podillia.

1

«Щедрик» М.

Леонтовича вперше надруковано 1918 р. у збірці «З народної

пісні». Того року, згідно з універсалом гетьмана П.

Скоропадського,

інтенсивно почали впроваджувати україномовну

культуру, науку й освіту.

“Shchedryk” by M. Leontovych

was first published in 1918 in the collection “From the Folk

Song”. In that very year, the Ukrainian-language culture,

science

and education began to be dynamically introduced, as

enacted by the Universal of Hetman P. Skoropadskyi.

2

Слід принагідно зазначити,

що в українській мові слова з літерою «Щ» вражають

особливою семантикою, пов’язаною з багатством,

плодючістю,

побажанням добра, як-от «Щастя»,

«Щедрість», «Щебетати» тощо, навіть наш

український «борЩ» – точно від «збориЩа»

всілякої городини. Любов до найвірнішої свійської тварини відчуваємо

в слові «Щенятко», а маленька сіренька птаха, схожа на

горобчика, яку можна побачити на Поліссі

та в Карпатах і що за

літній сезон двічі виводить пташенят, тобто – один раз, а потім

«Ще» й другий, прозвали в народі «Щедрик»,

маю на увазі

в’юрка канаркового (Serinus serinus).

It

should be noted that in the Ukrainian language, the words with the

“shch” letter strike with special semantics related to

wealth, fertility, wishes of good,

like in words “shchastia”

(happiness), “shchedrist” (generosity), “shchebetaty”

(twitter), etc., even our Ukrainian “borshch” (beet-root

soup) derives from the

word “zboryshche” (gathering)

of different kinds of vegetables. The word “shcheniatko”

(puppy) exudes love for the most reliable pet, and a small gray

bird

that resembles a sparrow, dwells in Polissia and the

Carpathians, and brings out nestlings in summer twice - once and

“shche” (again) the second time,

has received the name

“shchedryk”. The bird I describe is Canary Brambling

(Serinus serinus).

3

Висловлюю думку, що в

першодруці тексту в цій фразі закралася помилка, що, зрештою, стала

традиційною. Значно логічніше було б: «Хоч ЦІ

гроші –

то полова».

I assume that this phrase was misspelled in the

first print of the text, which ultimately became a conventional. It

would have been more logical to put, “If

THIS money, then

chaff.”

4 Про

це йдеться в документальному телефільмі «Щедрик» (реж. М.

Стогній, сценарист В. Качур, УТБ, 2011).

Documentary film

“Shchedryk” (director M. Stogniy, screenwriter V. Kachur,

UTB, 2011) describes this.

5

Особливо це помітно в

іноземних інструментальних або вокально-інструментальних

транскрипціях.

This is especially noticeable in foreign

instrumental or vocal-instrumental transcriptions.

6

Зокрема, дослідник із

Санкт-Петербурга Валентин Афанасьєв (скрипаль і художник) написав

полотна за скрипковою «Чаконою» Й.С. Баха та «Ave,

Maria»

Ф. Шуберта (соло з камерним оркестром), де, якщо спроектувати їх

через комп’ютер на монітор, курсором можна простежити кожну

ноту.

Specifically, Valentyn Afanasiev, a researcher from St.

Petersburg (violinist and artist) created canvases according to the

violin play “Chaconne” by J.S Bach and

“Ave,

Maria” by F. Schubert (solo with chamber orchestra), at which

each note is seen, if rendered to a monitor by computer and point the

mouse cursor.

Література

1. Леонтович М. Хорові твори / ред.-упоряд. [та передмова] В.В. Кузик. – К.: Муз. Україна, 2005. – С. 342.

2. Горюхіна Н. Гармонія в обробках народних пісень М.Д. Леонтовича // Українська радянська музика. – К., 1962. – Вип. 2. – С. 110–128.

3. Карась Г. Феномен «Щедрика» в обробці Миколи Леонтовича у світовому комунікаційному просторі ХХ ст. // Педагогічна освіта: теорія і практика. – Кам’янець-Подільський, 2012. – Вип. 12. – С. 343–347.

4. Леонтович М. Хорові твори. – С. 347.

5. Лосев А. Проблема символов и реалистическое искусство. – М., 1995. – С. 158.

6. Чегусова З. Роль символу, знака, міфу в професійному декоративному мистецтві України на межі ХХ–ХХІ століття // Українське мистецтвознавство. –

2014. – Вип. 14. – C. 146–147.